3 measures and 1 cut

- pennelloscalpello

- Jun 10, 2022

- 3 min read

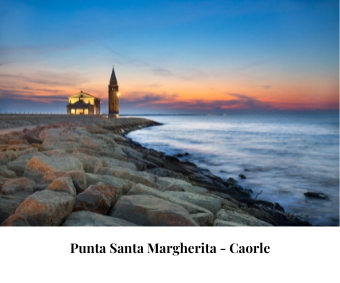

The very first word that comes to mind when talking about Avian craftsmanship is definitely “scalpellino”. Yes, because Aviano boasts a very old tradition of stone working, starting from its extraction in the quarry. Ferdinando "Nandino" Cipolat Gotet, the last remaining scalpellino, who represents the fourth (fourth!) generation of scalpellini in the Cipolat Gotet family, tells us about it. His family owned one of the three state-owned concessions that produced the famous Aviano Stone, a limestone that Nandino defines as gelina, meaning that it does not fear the cold, and tends to darken a bit over time. Do you know where you can find it? In the historical buildings of Aviano, in the bell tower, in the church, in the staircase of the Vienna Opera House, in the bridges of the Venice-Trieste railway line and in the breakwaters of Punta Santa Margherita in Caorle

Do you know how to choose the best stone blocks for a particular purpose?

Only an experienced scalpellino can know if a block is of good quality and therefore if it can be used for carving. It is all based on the sound of a few blows you give the block: if you hear a dull noise, then the block has cracks inside and cannot be used for carving.

...But does the scalpellino carve?

Not really: the scalpellino is specialized above all in the roughing of the block, that is to say he chamfers the block extracted by the quarryman giving it an initial shape and then leaves it in the hands of the sculptor who finishes it with the details.

It is a humble job as necessary and tiring. Since the years of the Republic of Venice (around 1600 A.D.), scalpellini have played a fundamental role in the construction of palaces and many architectural elements that are still recognizable in villages, such as the arches and beams of the entrances to courtyards marked with the year of construction and the initials of the scalpellino who made it or who commissioned the work.

All this required an enormous workforce and a lot of time, also because of the instrumentation that was used: just think that Ferdinando, Nandino's grandfather, in the 1950s was the first and only scalpellino in the area to have the silica sand helical wire to cut the stone, that is a "wire" composed of three cables twisted in a spiral inside of which flowed a mixture of water and silica sand that made it possible to cut the block at a speed of about 8 cm per hour... imagine that!

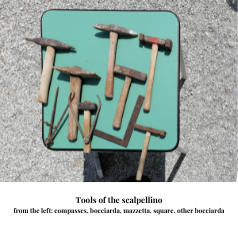

Obviously over the years the tools have evolved allowing a much more effective and faster extraction, but the best friend of the scalpellino will always remain the mazzetta or mallet, the typical hammer that every true stonemason owns, with which he began to carve the laip - the bowl for watering pigs - to gain confidence and learn to coordinate mallet and tip, with which he stole¹ the craft for which he was predisposed.

A job made of hard work, responsibility and a lot of attention. The scalpellino is taught to think well before acting, to measure three times to make a cut, because making a mistake means starting over again.

Where to find more scalpellini work these days:

marble: paving, tombstones, building cladding, kitchen countertops and more

Notes:

¹ learned by observation and trial and error

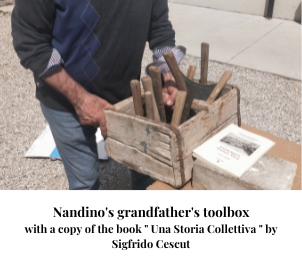

To find out more about Nandino and the story of his family we suggest the reading of the book "Una Storia Collettiva" by Sigfrido Cescut available at the Civic Library of Aviano

Comments